Anyway, Pierpont writes:

In 2009, on its fortieth anniversary, Portnoy was awarded an unofficial, retrospective Booker Prize, at the Cheltenham Literary Festival, for the best novel of 1969. A dissenting judge on the jury, the English classicist Mary Beard, complained about the choice in a Times Literary Supplement blog, deriding the book as "literary torture" and a "repetitive, blokeish sexual fantasy." She was met with a hail of reactions, pro and con, ranging from a heated defense of "the can't-put-it-down vigour of Roth's writing" to derisory comments about his "ethnic stereotypes" and the calmly universalizing assertion that "any man who's grown up in an ethnic-immigrant household in America has his entire life story etched out in the pages of that book" [65].I think the quotation I've put into boldface is highly revealing. Beard said, after all, that Portnoy is a blokeish sexual fantasy. ("Bloke" being Brit for "guy.")

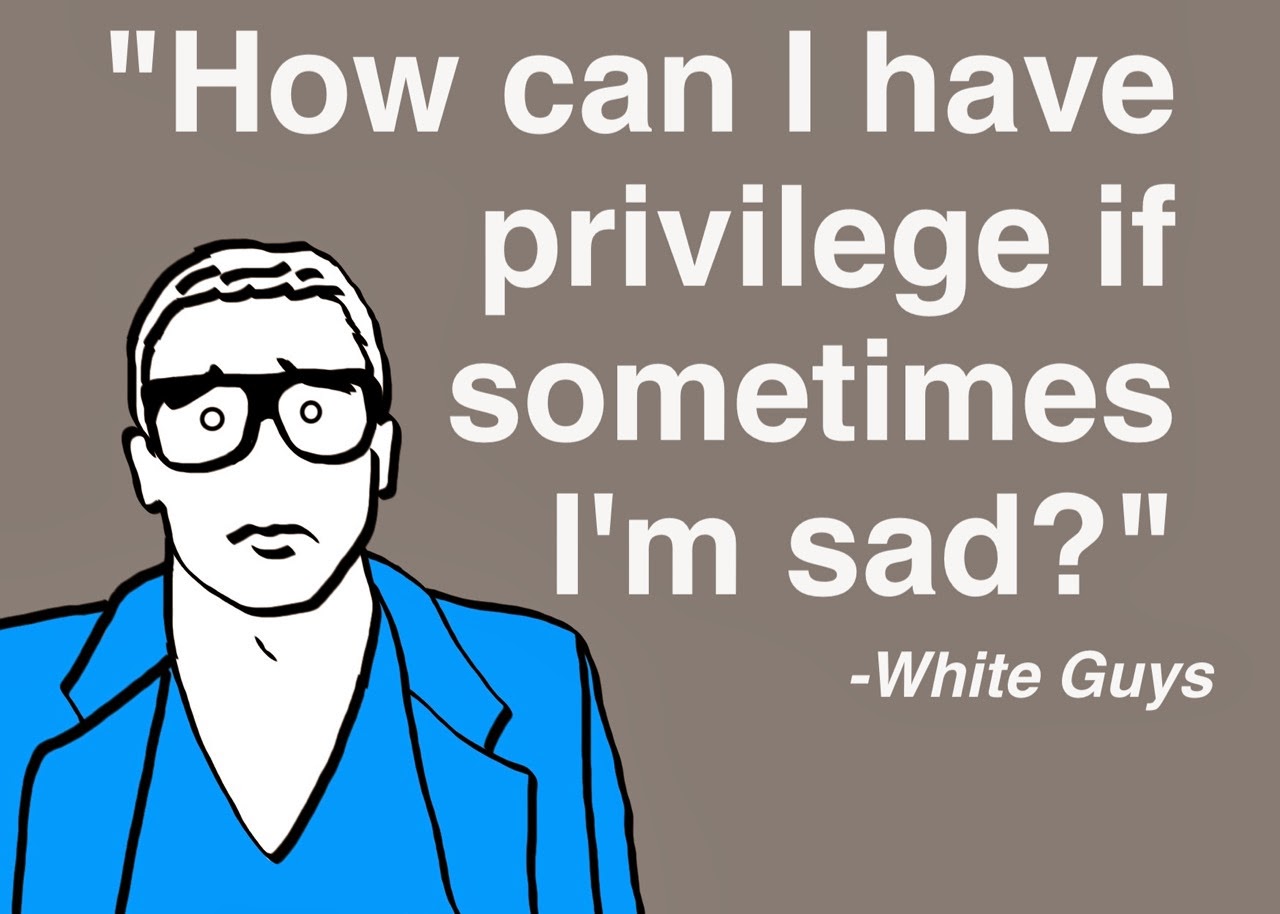

Even I, a queer American male who didn't grow up in an ethnic-immigrant household -- both my parents were several generations off the boat, and neither was Jewish -- found it easy to identify with Portnoy. But would a woman, most women, any woman feel the same way? Maybe; women grow up feeling constrained and limited by their upbringing too. But women are the problem in Roth's book: the mother, the dull sister, the crazy hillbilly girlfriend, the numerous WASP girlfriends, the tough Israeli woman before whom Portnoy is impotent. It's possible, and desirable, to identify with characters of the other sex: women have been doing it for millennia, and more men do it than is usually recognized. But it gets old after a while, and the most determined, sympathetic female reader might be disturbed at last by the role women characters play in Portnoy's Complaint. Considering that women are just over half the population, their reactions to art and entertainment ought to count for something. Any woman who's grown up in a male-supremacist society -- meaning all of them -- might begin to wonder why her life story isn't etched out in more pages, and get tired of seeing women treated as the adversary Others all the time.